A little experiment here – in the stream of consciousness style, I write. I’ve been researching Kerouac for the last couple of weeks, and I find that the more I find, the more I want to find. This author captivates me, and that may have something to do with his unconventional attitudes about writing and life. Take this quote from his book Lonesome Traveler for example:

The stars are words and all the innumerable worlds in the Milky Way are words, and so is this world too. And I realize that no matter where I am, whether in a little room full of thought, or in this endless universe of stars and mountains, it’s all in my mind.

That’s romance. Beatific romance.

Kerouac was a pioneer, and he preceded his gang, which included (most notably) Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. He embodied the voice of an American generation: the Beat Generation. Be-at, beat, tired, beatific, stumbling through poverty and into happiness, or as Jack put it: “crazy, illuminated hipsters suddenly rising and roaming America, serious, bumming and hitchhiking everywhere, ragged, beatific, beautiful in an ugly graceful new way.” Jack sought the beyond: he wanted to know more about what made life real, and to do that, he decided to travel and write. He traveled for seven years.

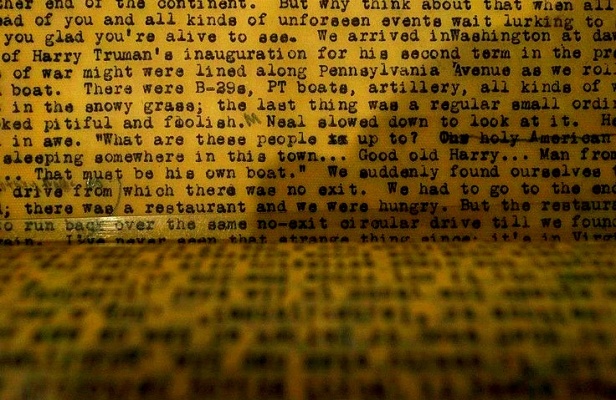

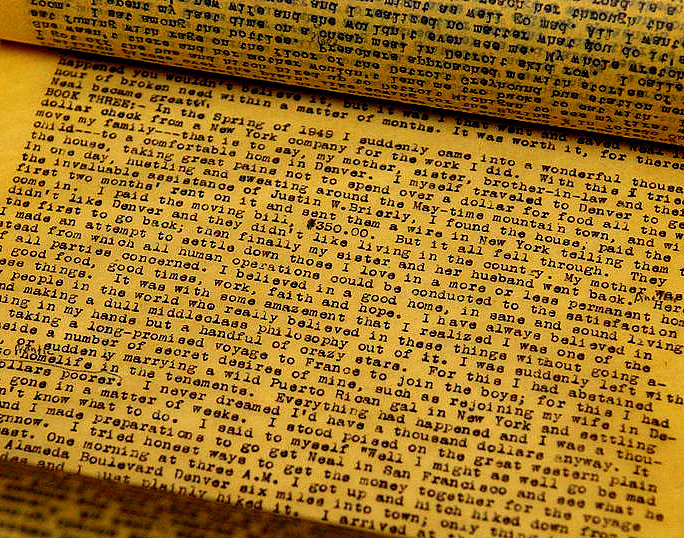

On the Road made Kerouac a household word in the late 50s. It took him only three weeks to produce (plus seven years if you count the traveling) and he wrote on a continuous scroll in the stream of consciousness style, which he learned from James Joyce.

I woke up as the sun was reddening; and that was the one distinct time in my life, the strangest moment of all, when I didn’t know who I was – I was far away from home, haunted and tired with travel, in a cheap hotel room I’d never seen, hearing the hiss of steam outside, and the creak of the old wood of the hotel, and footsteps upstairs, and all the sad sounds, and I looked at the cracked high ceiling and really didn’t know who I was for about fifteen strange seconds. I wasn’t scared; I was just somebody else, some stranger, and my whole life was a haunted life, the life of a ghost.

from On the Road

Here are a couple of samples.

It turns out that Jack was always a traveler, even from an early age. At sixteen, he went to Columbia University in NYC on a football scholarship. Eventually, he dropped out and returned to Lowell, Massachusetts, his home town. That didn’t last long though. One day, he got drunk and enlisted in the Navy, Marines, Coast Guard and Army, all at the same time. He ended up on a ship, and although this incident illustrates his impetuous nature, it has little to do with the most significant part of this story, which is coming up next.

It turns out that Jack was always a traveler, even from an early age. At sixteen, he went to Columbia University in NYC on a football scholarship. Eventually, he dropped out and returned to Lowell, Massachusetts, his home town. That didn’t last long though. One day, he got drunk and enlisted in the Navy, Marines, Coast Guard and Army, all at the same time. He ended up on a ship, and although this incident illustrates his impetuous nature, it has little to do with the most significant part of this story, which is coming up next.

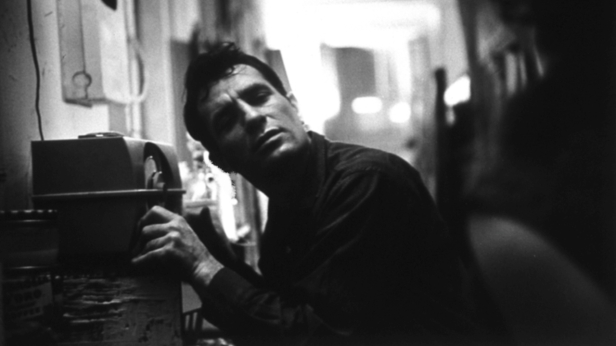

He is more beautiful than Marlon Brando. (Salvador Dali)

Kerouac becomes even more intriguing when placed in the context of his Franco-American heritage, and this is the angle from which I choose to illuminate him.

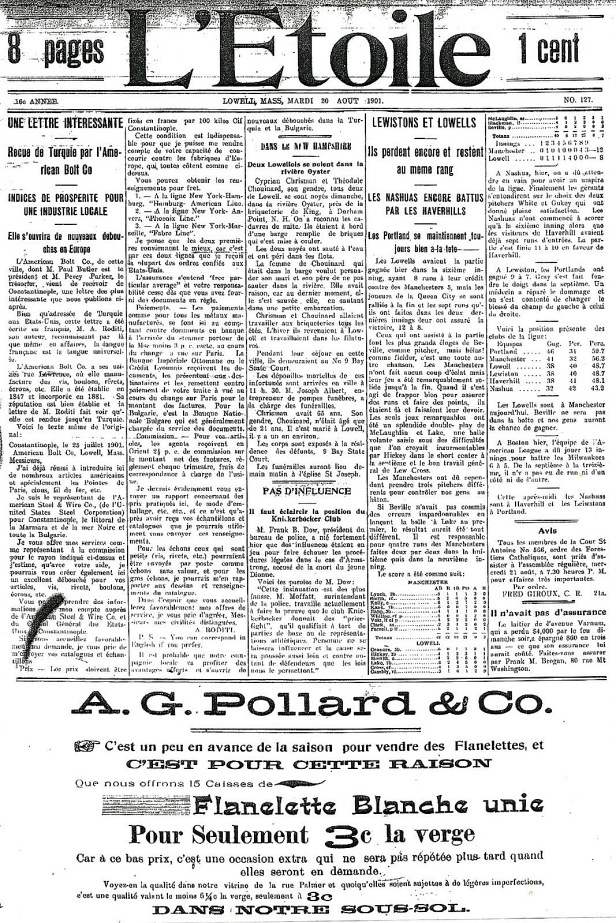

Jack’s parents immigrated from Quebec, Canada in the early 1900s, along with thousands of other Franco-Americans. They settled in le petit Canada, a region of the northeastern United States, which includes parts of New Hampshire, Maine, Massachusetts, and Vermont. His native language was French, and more specifically, he spoke in joual, which is a type of nonstandard Québécois slang. In Quebec, this has historically been considered “low-brow” and non-literary language. Jack didn’t learn English until he was six, when he started school.

Kerouac initially planned to write in his native language, but because joual wasn’t widely accepted in Quebec, he decided he would have more success writing in “nonstandard” English. At the time, Americans were more receptive to his unconventional and “wayward” use of colloquialisms and invented words, so he went with it. The significant piece in all of this, however, is that Jack first formed his thoughts in French, and he later translated them into English. Why is this significant? Well, I can’t cover it in a single blog post, so I will just plan to continue pursuing that question. In the meantime, here is an example of Jack’s native speech. (Note: In this example, he has been drinking.)

Here you may find a longer version sans subtitles. Jack discusses the origin of “Beat” and the “Beat Generation” in French.

Recently, two of Jack Kerouac’s manuscripts were discovered by a librarian in Quebec. One is called La Nuit est Ma Femme (The Night is My Wife), and the other is called Sur le Chemin (On the Way), a precursor to On the Road. Both novels are due to be published by the Canadian publisher, Les Éditions du Boréal, in Spring 2016.

In addition, there are a total of two known researchers who study Jack Kerouac’s bilingualism. They are his former girlfriend, Joyce Johnson, author of The Voice Is All: The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac, and UNC French Professor Hassan Melehy, whose book Kerouac: Language, Poetics, and Territory will be published by Bloomsbury in 2016.

And one last quote to live by.

He saw that all the struggles of life were incessant, laborious, painful, that nothing was done quickly, without labor, that it had to undergo a thousand fondlings, revisings, moldings, addings, removings, graftings, tearings, correctings, smoothings, rebuildings, reconsiderings, nailings, tackings, chippings, hammerings, hoistings, connectings — all the poor fumbling uncertain incompletions of human endeavor. They went on forever and were forever incomplete, far from perfect, refined, or smooth, full of terrible memories of failure and fears of failure, yet, in the way of things, somehow noble, complete, and shining in the end.

from The Town and the City (1950)

M. Chaplin

Fabulous and splendid bio of one of the 20th century’s great writers. I was exposed to Kerouac in high school (it was an alternative high school and my adviser-teacher Michael handed me “On the Road” and said, “You need to read this.”) and quickly began to absorb everything he wrote. Thanks for bringing facets about the man I didn’t know or knew just in passing. The last quote from “The Town and the City” was the one I read after on the road, and was easier, because of its more traditional novel-format, for me to “get.” Over time I was able to appreciate more deeply his works like “On the Road.”

LikeLike

Thanks. I was really excited to learn that his native language was French, and his French books will be published soon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay. First off, your webpage is extremely, brilliantly set-up. Second, this Kerouac stream-of-consciousness blog post is better than 90 percent of the articles I have ever read on the artist, or his novels. The idea of writing in his style helped me to be drawn into the subject matter, since it was about Jack; and it felt quite like Jack. The sentence structures and the use of lists were a couple things I noticed that contributed to this, but, most of all, it felt natural–like Jack.

I keep scrolling up and re-reading each of the sections. This seriously a bad ass post, Michelle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! It’s so awesome to read your response to it!

LikeLike

Of course. I wish I would have been paying more attention to these blogs before because, seriously, your choice in artists is spot on. And they’re cool and fun subjects. It really is a well done blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person